Mara Reed

Mara Reed is a student at University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire currently completing her research at Boise State University under Dr. Dylan Mikesell.

As part of an ongoing DOE funded project to find and assess potential geothermal resources in Idaho, the Camas Prairie-Bennett Hills area near Fairfield has been selected for further investigation. I will be working with researchers from Boise State to tackle the assessment from a seismic standpoint using both passive and active source methods. The passive source data comes from IRIS and will be reanalyzed for small earthquakes; if possible, their focal mechanisms will be determined. We will collect several tracks of active source data using an accelerated weight drop to obtain reflection imaging up to about one kilometer deep. Our main goals are to locate faults and fluid pathways, characterize the lithology of the subsurface, and determine the extent of microseismicity in the area. These three things will contribute to an overall geothermal resource evaluation.

(Seismic) Reflections

August 3rd, 2016

You know, for reflections that shake you to the core.

Heh.

So, it's the final week, and I find myself wishing for more time. School begins one month after I return home and I can't wait to get more Yellowstone in my system, but perhaps I would have benefitted from an extra week in Boise to tie up the loose ends. I will spend more time preparing the poster during the fall than I had originally planned; even so, I am not too worried. We shall see how easy it is to put my research on the shelf and then take it out again in September or October. I plan to engage with my newly bestowed seismology textbook between now and then so that geophysics does not completely leave my mind.

At the beginning of my internship I posted some goals to this blog, and I want to comment briefly on the progress that has (or hasn't) been made on them.

- Determine if geophysics is an appropriate career path for me. After a solid two months of immersing myself in the world of geophysics, I have nurished an affinity to the field and will likely pursue it in grad school. I think I will always ponder the roads not taken, the what-ifs or might-have-beens. Every once and a while I get a nagging feeling about astronomy (we just confirmed gravity waves; what a time to enter that field!) or solar physics, and planetary science is still on the table. However, I predict that fieldwork will be an important part of enjoying what I do in life, and the chance of me being able to set foot on another planet is low. Too much of the world (and our universe) is intriguing, and there is never enough time to study it all. The best I can do is to pick a few mysteries of my own to solve, strive to bridge the gaps between disciplines whenever possible, and be content with passing glances of the mysteries I cannot court.

- Acquire a comfortable working knowledge of passive and active source seismology. Depth of knowledge will come with time. Though I am not yet comfortable, I feel I grasp the basics well enough to foray into the field of seismology and not immediately trip over a fault scarp.

- Gain experience with Python, ObsPy, and ProMAX. Due to various issues on the passive side of my project, I did not spend much time with ObsPy this summer. I have a good starting point with Python in general and plan to continue building my coding skills. ProMAX is no longer foreign to me. I still feel more comfortable with a guide through that software, but can flail about and process some types of seismic data with minimal assistance now.

- Improve skills related to research. The process of research comes more comfortably to me now, and is not the behemoth I imagined it to be. I'm well on my way to proficiency with academic writing. I find it difficult to avoid passive voice while at the same time not starting every sentence with "we" at times.

- Network with other geoscientists. Talking to experienced scientists is difficult, but putting myself out there has already allowed me permission to tag along on a BSU professor's research visit to Yellowstone. My list of people to meet at AGU is growing.

I feel that I have grown and matured in the past two months and am excited to apply my new skills to future projects. I'm also eagerly awaiting AGU which will place the cherry on top of my IRIS experience by being the first professional conference I ever attend. I look forward to seeing my fellow interns and appreciating all they have accomplished.

The future awaits.

Under Pressure

July 27th, 2016

We've found a problem with our automatic picker - it doesn't handle multiple events in rapid succession very well. Checking our earthquakes against the INL catalogue reveals multiple occurrences where our events match the time of INL events but are in completely different locations. Checking the automatic picks on the events in question show inconsistent picking when there are multiple P-wave signals coming in. We wanted to be running the matched filter for our Camas Prairie events to find more earthquakes near Fairfield at this point, but we need to fix this kink first.

I think the most difficult challenge for me this summer was asking for help when I needed it. My instinct is always to struggle with something until I figure it out, and I never want to appear incompetant. When you know a subject well and are trying to explain it to others, it is very easy to skip over details that you think are perfectly clear but may not be clear to others. This summer I definitely had to get used to the idea of asking what felt like stupid questions so that I could fully understand the work that I was doing. I'm currently struggling through rapid data interpretation so that I have some numbers to tag onto my abstract. With my active source mentor in Singapore and my passive source mentor at a conference, I've often felt lost this past week while trying to push through the final part of my project. Everything feels a little overwhelming; I don't have much time left and I'm definitely feeling the pressure.

To deal with these challenges I've adopted a radical acceptance of feeling a little lost. Research is the process of gathering up all your puzzle pieces and putting them together. Usually you don't have a picture of what the puzzle is supposed to look like. Often there will be missing pieces, and occasionally you find a piece that doesn't belong to your puzzle - but maybe somebody else can fit it into theirs. As a newcomer to geophysics, I don't yet possess all the knowledge or tools to conduct research easily. That is why I'm an intern, why I have mentors and peers. It's okay to ask questions or for clarification and to admit when I'm confused. True comfort in the field will come with experience. So, instead of becoming exasperated, I'm pushing through my last few days and solidifying my knowledge of my research and of geophysics. That abstract deadline is a little menacing, but it will get written. Onward!

Locating Earthquakes and a Look at the Office

July 18th, 2016

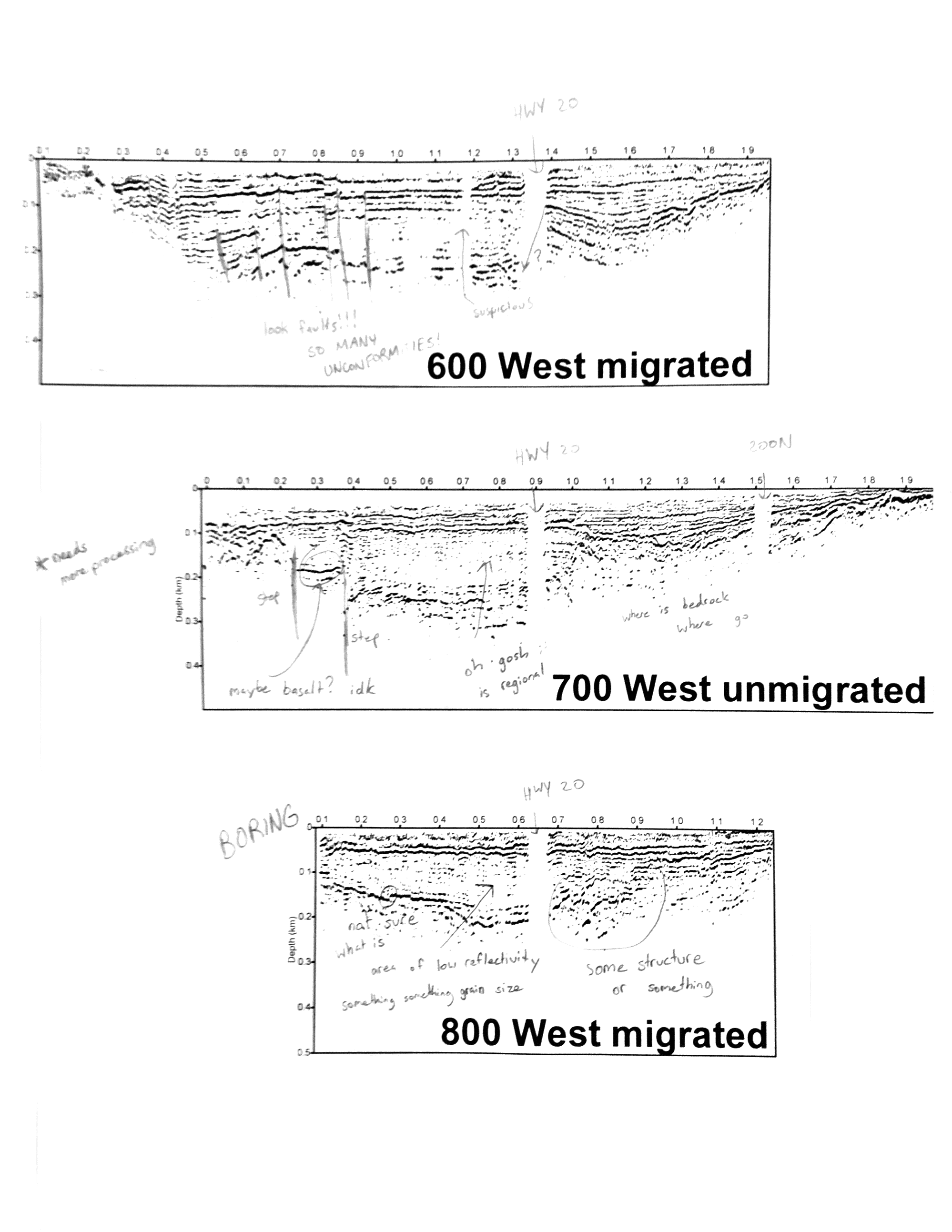

The active source side of my project has now reached a stopping point. As a representation of my work thus far, here are totally professional interpretations of three images I helped create.

Obviously, I have some more work to do - I need to complete an actual interpretation with the aid of local well logs, finish processing 700 W, and check in with some of the grad students here about the two other lines of data. Then I'll be able to finish up with a map showing the new faults. While I've started to compile some summaries of the data aquisition and processing, the process of formatting everything for a poster will occur after my internship is over. Lee wants to collect some more active source data in the early fall and I may be incorporating some of those findings into my poster.

My last three weeks will be spent locating earthquakes using the NonLinLoc program on sets of events picked by automatic triggers in ObsPy. So far I've just familiarized myself with all the syntax and completed event locations for the first three months in 2007 - I found just one earthquake in the Camas Prairie area. We will continue to locate events until we've found some closer to Fairfield, and then search through IRIS data again for more events using the Fairfield earthquake waveforms as templates. Best case scenario: we find some earthquakes that we can map to the faults discovered by the active source survey. Worst case: we can't locate any earthquakes near Fairfield at all and I will be unable to corroborate our active data with passive data.

I work in the Environmental Research Building here on Boise State's campus. Incidentally, it's a PokeStop in Pokemon GO - I can stock up on items while my code is running. The foothills of the Boise Mountains are in view from the geophysics department on the 3rd floor. I've taken over a grad student's desk (he's elsewhere for the summer) inside a cubicle.

I bring my laptop back and forth from the office every day. In addition to a healthy grad student population, we also frequently have furry friends.

The corgi puppy is named Thor, and he is my favorite distraction.

The time has passed quickly in Boise. My environement no longer feels new and my apartment feels like home; in just three weeks I will be leaving Boise and moving on to the next adventure. Of course, my IRIS experience won't completely leave my mind - I want to stay on top of my preparations for AGU and have my poster in order well before December. That's the plan, anyway.

Geyser Interlude

July 12th, 2016

Happy belated Independence Day! I was lucky enough to get a surprise opportunity to travel to Yellowstone National Park with a friend over the July 4th holiday. Leaving the trials of active source data processing behind for a moment, we traveled across Idaho and finally entered the park through West Yellowstone, Montana. Amazingly, no bison traffic jams impeded our progress toward the Old Faithful area.

We are both "geyser gazers," otherwise known as crazy people who stare at holes in the ground for the chance to see inverted intermittant waterfalls. While I enjoy Yellowstone for its wildlife, wildflowers, scenery, and many hiking opportunities, geysers take the cake. There is a whole community of gazers; I'd estimate we number near 1000 or so. We are most concentrated in the Old Faithful area, but one might also find us at Norris or in the Lower Geyser Basin. Together we enjoy watching geysers and recording observations about the thermal features in Yellowstone. We use FRS radios to communicate geyser activity to each other and the National Park Service.

Why geysers? It's certainly a strange hobby. For some, there is a social appeal - though our community as a whole is pretty loose, the regulars form solid friendships with each other and get to catch up every summer. For others, it's the puzzle. While geysers are by nature unpredictable, almost every single geyser exhibits something that gives a careful observer more information about when it is likely to erupt or if it has erupted recently. Old Faithful is famous for its predictability. Preplay splashes signal the geyser will soon erupt, and the duration of the eruption predicts the next interval - 94 minutes or 60 minutes until the next eruption. In contrast, there are geysers that are wildly unpredictable but show complex signs of when they might erupt.

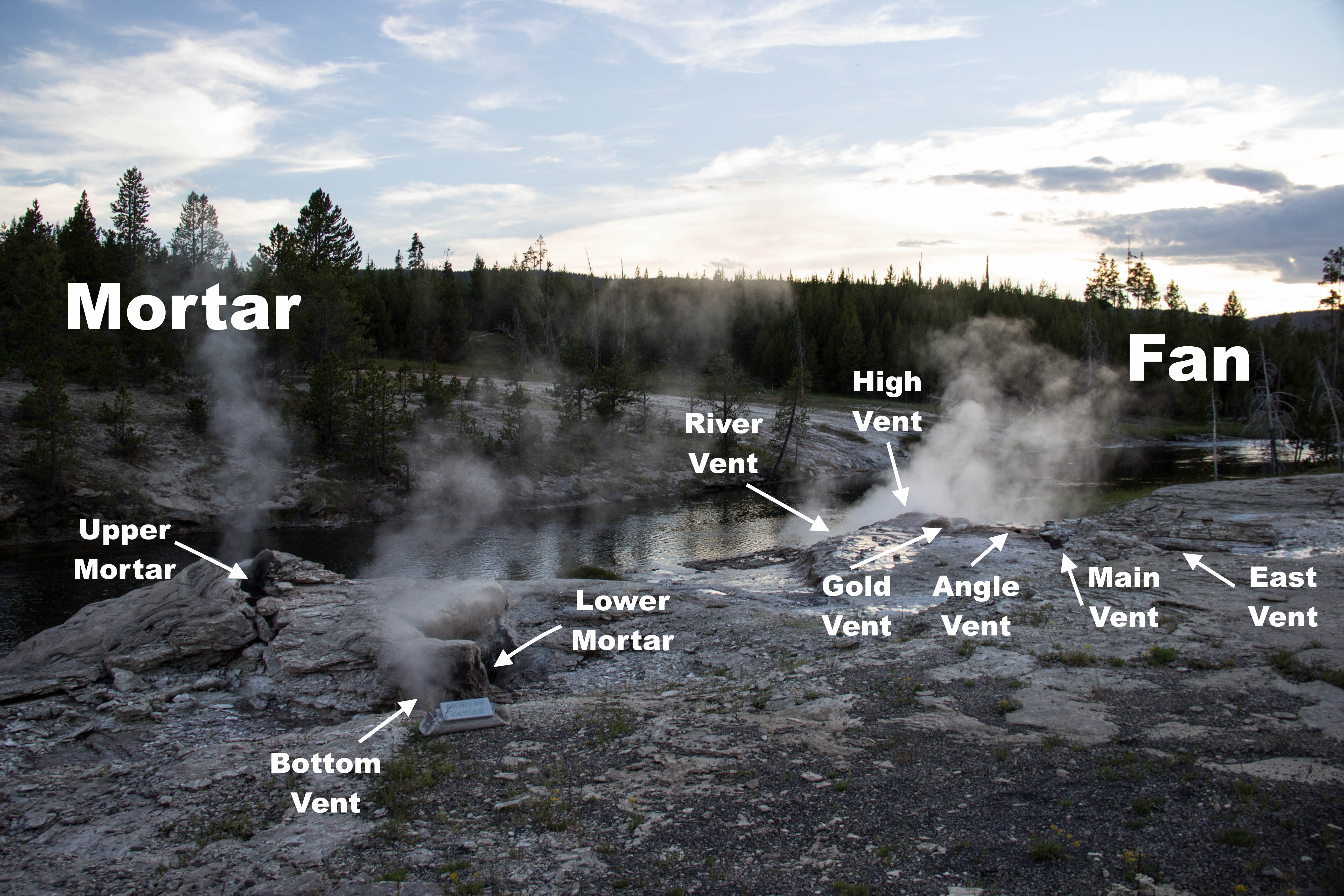

Let me walk you through the basics of Frustration and Mortification, ehem, I mean Fan and Mortar Geysers. These two erupt together and when active, the intervals typically fall every 3-7 days. Here's a labeled photo for reference.

Normally, Fan goes through cycles in which its vents turn on in a certain order. After a quiet period (during which Mortar may splash lightly from Bottom or Lower), River Vent turns on. River actually erupts horizontally, away from your perspective in the photo above - so figuring out when River is on either involves using heavy steam as a proxy or walking 100 meters up the path to the bridge where you can get a clear view of it. High and Gold begin to splash and are considered on when the splashing becomes nearly constant. Finally, Angle turns on with a swishing sound. The cycle ends when River turns off again - a single cycle can be anywhere from 20 to 70 minutes, typically.

Every once and a while, an event cycle occurs, simply meaning something different happens. Here's where things get complicated. Main Vent is not a friend to Fan's other vents, and splashing in Main Vent often leads to pauses in activity from the other event. Here's a timeline for what we might consider an "ideal" event cycle:

Main Vent splashing.....River Vent on.....River Vent pause.....River Vent on.....River Vent pause.....River Vent on.....no more Main Vent splashing.....High/Gold Vents on.....Angle Vent on

The final component needed for an eruption is called lock. In lock, High Vent erupts steadily to a height of 1.5-2 meters (5-6 feet), and Gold/Angle Vents splash continuously. An eruption may be initiated from East or Main Vent, or in Upper Mortar. Soon all the vents take off. Upper Mortar reaches 23 meters (80 feet), Main Vent hits over 30 meters (100 feet), and East Vent shows off an impressive horizontal throw that will absolutely get you wet. The following photos are from a particularly strong eruption on August 12th, 2014. Note the drenched people and the beautiful jets from Upper Mortar.

Unfortunately, perhaps only 5% of event cycles turn into an eruption. Some event cycles are considered more promising than others, and there are so many variations (for example: no Main Vent splashing but pause(s), 3-4 River vent pauses, Gold pauses, full Bottom Vent eruptions, no lock/terrible water levels in Fan but serious energy in Mortar). Yet even on the "best" event cycle, Fan and Mortar might not erupt. Not even a lock will guarantee you an eruption. Event cycles are adrenaline-filled events for geyser gazers as we wait, watch, and hope. During active periods, gazers take shifts at Fan and Mortar to watch for event cycles and call notable activity on the radio.

My recent trip saw a particularly frustrating sequence of frequent, great event cycles that just seemed to fizzle out. At the nine day mark since the last eruptiopn, most of us had given up trying to catch them and were worried they might be going back into dormancy, but - surpise! - they erupted during a thunderstorm on the 4th of July. Grey on grey, but tons of fun to catch an eruption on such a short trip.

We gazers speak very casually of surface behaviour "causing" a geyser to erupt, but what's going on under the hood is still a mystery. A solid hold on surface activity is only the beginning. For true understanding of geyser periodicity, we must investigate the structure of plumbing systems and the physics and chemistry behind superheated water and whatever happens to be dissolved within it. The USGS recently found evidence that dissolved carbon dioxide plays a role in triggering geyser eruptions. Geophysical techniques are already being used to investigate the dynamics of Lone Star Geyser and as a method to detect/record eruptions (shoutout to IRIS alumni mentor Rob Anthony who worked on that study). Hopefully, I'll get to study geysers during my career - and maybe even connect the citizen scientests among the ranks of geyser gazers to interested researchers from academia in the pursuit of geyser research.

Your regularly scheduled IRIS intern programming returns next blog.

A Preliminary Look Underground

June 27th, 2016

I wrapped up my last active source fieldwork last week with another three days in Fairfield - despite bringing my DSLR, I was unable to get photos of any of the wildlife out there. We did find several skittish fox when scouting out one of our dirt roads as well as a barn owl and a golden eagle pair. I've been asked a few questions about what our streamer looks like, so I thought it would be easiest just to share a photo. All of the geophones are wired through the streamer. Metal plates at each instrument help weigh the entire streamer down and allow the geophones to be screwed in to achieve coupling with the plates and the ground. There is more data aquisition to do out there, but we're resigned to waiting for good weather days now. From here on out I will be working on data processing and focusing on the active source side until mid-July.

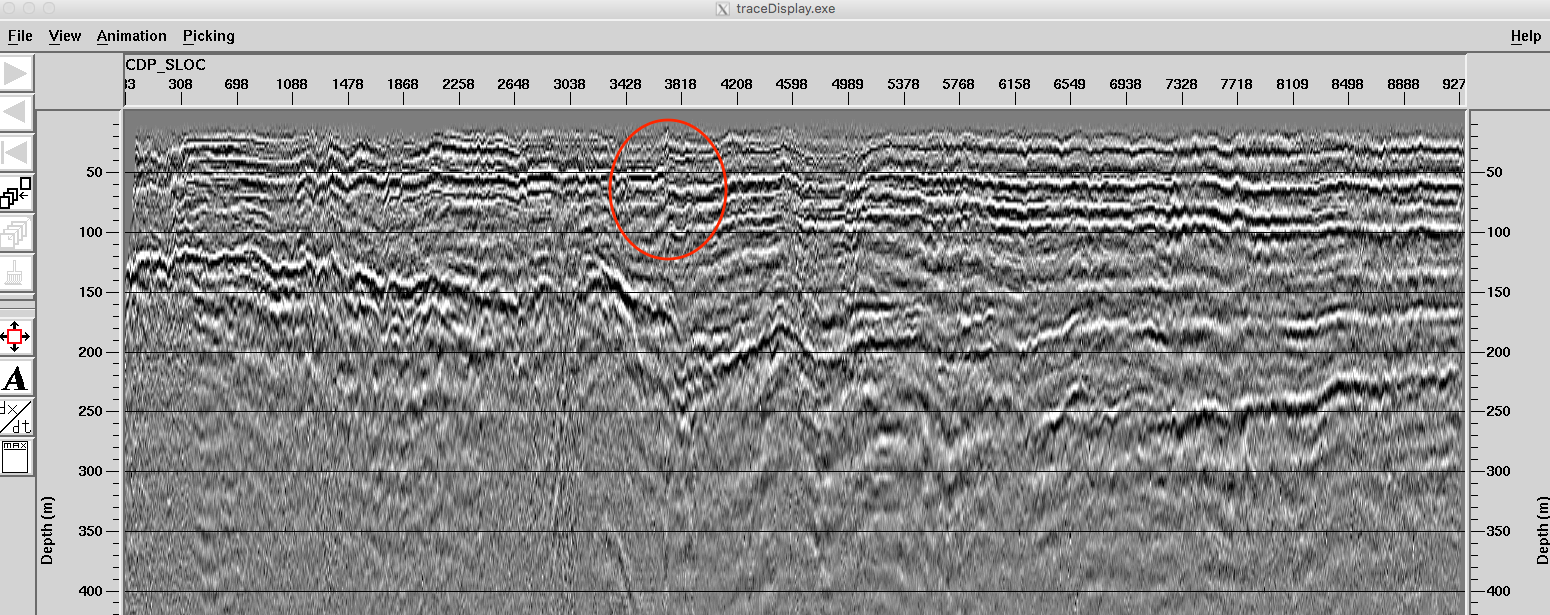

I'm beginning to look at reflection data from our only E-W line and completing a preliminary analysis. After killing bad traces/shots and acquainting myself with common midpoint gathers, velocity analysis, and normal moveout adjustments in ProMAX, I've r an early look into the shallow subsurface below our line. The bedrock is easily followed on the west (left) side of the image but sort of loses coherency on the east side. I'll have to play around more with the data to see if I can create a better picture.

The circled area is interesting. There is definitely an unconformity there and we suspect it's an active fault (moved in the last 10,000 years) with little surface expression other than a nearby stream. If so, we're the first people to image the fault using active source techniques. I suppose this is what it feels like when research goes well!

This week I prepared a ~45 second "elevator speech" to give to someone interested in my summer research. I've already had to think about this during my fieldwork; the dirt roads we are working on see local traffic and people often stop and talk to us about what we're doing. The first few times I let others on my team answer the locals' questions and then slowly developed my own summary and got into some great conversations with ranchers about their personal experiences finding hot water in the area. I definitely became more confident through repetition and as my own understanding of our work grew. Thus developing the formal version felt easy; I took out the fieldwork details and added in a few sentences about the passive source side of our investigation and - tada! - I had a bite-sized overview of my work that I could modify slightly for different audiences. This will be useful for AGU and anytime I'm asked about what I did this summer. Despite the immense training we will receive in our field, communication skills can be left in the dust. The ability to convince someone else, lay or educated, to care about your research is what makes an effective scientist. And those grant proposals certainly don't write themselves!

I'll leave you this week with a few photos from an excursion to Jennie Lake and Peak 8610 in the Boise National Forest.

Data Quality, Networking, and an Unexpected Adventure

June 17th, 2016

What's a major source of noise in seismic data? The answer, my friend, is blowin' in the wind.

I've just come back from another three days in the field collecting active source data, and things definitely didn't run as smoothly as last week. Our first problem was the incessant wind. Normally, geophones are planted firmly into the ground to avoid as much wind noise as possible, but we are dragging a streamer of geophones. The streamer is weighted with metal plates to help mitigate some of the wind noise, but once the wind picks up to a steady 10-15 mph, the data just looks like a mess. I'm told that processing and filtering the data can clean things up a bit; still, that takes time! High quality data is extremely important for picking first arrivals and reflections. When possible, it is better to take more time to collect good data - rushing through the collection only means more time spent in processing.

So, we decided to stop early on Tuesday. After throwing some epoxy on holes in the streamer and packing everything up, it was only 4pm. We grabbed a quick bite to eat in Fairfield and then took an impromptu trip up into the Sawtooths. A gorgeous three mile hike up Big Smokey Creek took us to Skillern Hot Springs. A nice little pool forms at the base of a light waterfall formed by hot water pouring out of the rock above. Wildlife included a grouse, bald eagle, mule deer, a marmot, and pronghorn. I'll have to start bringing my DSLR into the field in case we go on any more hikes or see any more baby pronghorn while hammering out our lines in Fairfield.

On Wednesday we competed with noise from large farm equipment carrying hay bales. Again we were stalled when we approached a busy intersection at the field where the hay bales were stacked. Besides dealing with noise, we wanted to be courteous to the farmers and not block the intersection for half an hour while we dragged our streamer through. While we waited, I took the time to call Dr. George Veni of the National Cave and Karst Research Institute. He was able to offer some insights on how I might pursue multiple research interests and how geophysics is being used to investigate karst systems, one of my research interests. I'm amazed at how easy it is to connect with people once getting involved in an organization like IRIS - you're only one or two degrees of separation away from scientists you've never dreamed of meeting.

Thursday brought more wind and a technical mishap. The magnets that had been welded onto the weight drop broke off, fully disabling our automated program for weight drop control. This meant one of us had to climb in the back of the van and pick up the controller. I actually didn't mind doing this, but the white noise from the motor and the monotony of slowly counting to four started putting me to sleep. We finished our line in the evening and got the go ahead from Lee to pack up and come home. I got to ride in the back of the mule (kinda like a golf cart) with the streamer to keep it from falling out while we drove it back to camp. 25 mph feels like 80 when you're standing up on a moving vehicle with the wind whipping through your hair. It was exhilirating - what can I say, I enjoy the simple things. All this fieldwork is giving me incredibly valuable experience using technology to collect data; by the end of my internship I think I'll be very comfortable with the whole active source data collection process.

I haven't had much time to work with Dylan on the passive source side of this investigation yet. I won't be the first person to see the seismogram data for Fairfield, but I likely will be the first to process it for small earthquake detection. Active source fieldwork will take up the majority of June and then I can power through both active and passive source data analysis in July. The summer is already going by so quickly and there's still so much to do!

Fieldwork and Goal Setting

June 13th, 2016

I'm about to start the fourth week of my summer by beginning to use Excel to organize data. Last week I spent a three day stretch in the field collecting active source data using an accelerated weight drop and Lee Liberty's streamer method. Generally, active source data is obtained by planting a line of geophones (seismic instruments) and leapfrogging them once you've hammered the ground every few meters down the line. Lee wires his geophones through an old firehose that we tie to the back of the van/trailer with the accelerated weight drop. We have two streamers with geophones at different spacings that hook onto each other. Setup can take up to two hours (those streamers are not light and long cables have a tendency to become tangled) but then you're home free until you have to pack up. Only one person needs to be in the van; they drive and run the seismic software on a laptop. A second person keeps the streamer from migrating into the ditch and fields questions from curious locals who (understandably) want to know what the heck we're doing. Extra personnel can catch on reading, take a nap, or sit and enjoy the view - active source data collection at its easiest.

With tens of kilometers of dirt roads to cover, data collection takes a long time and we plan to be out in the field for at least three days every week in June. Four hits every four meters can definitely become monotonous and we can only move at at a 400 meter/hour pace. But I'm working with a fun crew, which makes all the difference.

I also wanted to take a moment to outline my goals for the summer. I applied to be an IRIS intern primarily to explore a possible career in geophysics and gain research experience, but after getting acquainted with my project and the world of seismology at large, I feel I can expand upon those initial motivations. Here is the goals list, version 2.0:

- Determine if geophysics is an appropriate career path for me. My main research interests right now include hydrothermal systems, geyser periodicity, speleology, and planetary science. I will likely have to narrow those interests before heading into grad school and pursue a degree most useful in researching them. This worries me a little bit; specialization could lock me into a field that I figure out I don't actually enjoy that much. Geophysics, as I am learning, has broad applications and might allow me to specialize while keeping a generalized training applicable to all the fields I'm interested in. I think I will have a better idea of what field I want to enter in grad school after the end of this internship.

- Acquire a comfortable working knowledge of passive and active source seismology. This includes understanding techniques as well as the physics behind what I am doing.

- Gain experience with Python, ObsPy, and ProMAX. These are the main programs/languages I will be working with this summer. I want to be able to independtly use them to solve new problems by the end of my internship.

- Improve skills related to research. Specifically, I would like to improve my academic writing skills and become acquainted with ways to assess progress in research.

- Network with other geoscientists. I already started doing this at the IRIS orientation and hope to continue meeting geophysicists and others as I work at BSU and go to AGU in December.

The End of Orientation

June 3rd, 2016

This past week I have been spending time at New Mexico Tech in Socorro, NM with the other IRIS interns. We have been having plenty of adventures together, from stumbling through seismometer installation to hiking in the Magdalenas. Tomorrow, most of us will head off to our host institutions and start on our respective projects.

I'll be using this blog to keep a record of my progress over the next two months.