How does an earthquake early warning system work?

An earthquake warning system uses existing seismic networks to detect moderate to large earthquakes. Computers, communications technology, and alarms are devised to notify the public while an earthquake is in progress. This is not the same as earthquake prediction. Data from the 2011 Tohoku, Japan earthquake taught us much about mega-thrust earthquakes. In its simplest form, an earthquake early-warning system assumes the earthquake results from sudden slip on a small area of a fault surface, and the initial magnitude represents that motion. But for earthquakes greater than magnitude 7, that small patch at the epicenter is just the starting point for a rupture that spreads over a huge area as it tears the fault and radiates immense seismic energy. In this animation we can see how ground motion, measured by GPS, can enhance earthquake early warning.

This animation was made by UNAVCO in collaboration with the Cascadia EarthScope Earthquake & Tsunami Education Program CEETEP and IRIS. The animation with related resources can be found on the UNAVCO site.

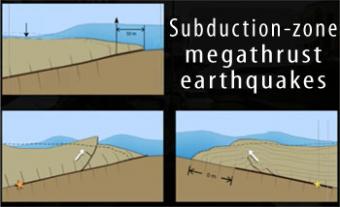

Subduction-zone megathrust earthquakes, the most powerful earthquakes in the world, can produce tsunamis through a variety of structures that are missed by simple models including: fault boundary rupture, deformation of overlying plate, splay faults and landslides. From a hazards viewpoint, it is critical to remember that tsunamis are multiple waves that often arrive on shore for many hours after the initial wave.

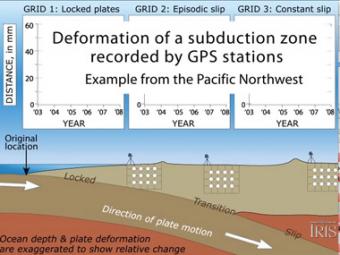

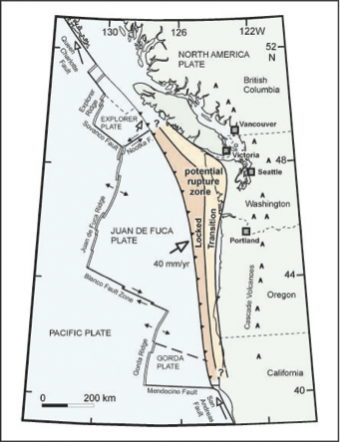

Subduction zones show that there are 3 distinct areas of movement in the overlying plate:

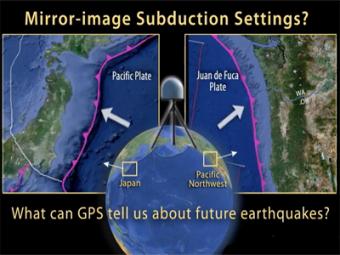

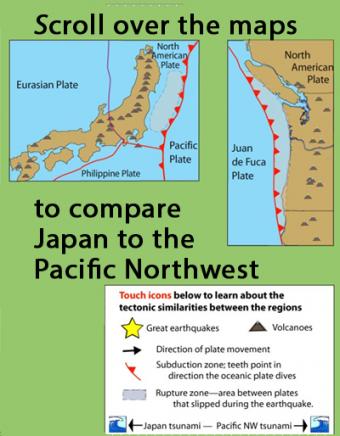

This UNAVCO animation compares Japan's subduction zone at the location of the 2011 earthquake with a mirror-image subduction zone in the Pacific Northwest. There are many similarities.

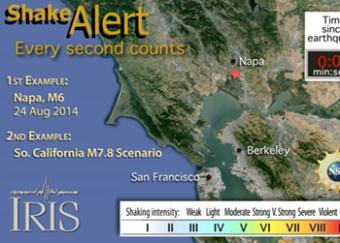

ShakeAlert (www.shakealert.org) is an experimental earthquake early warning system (EEW) being tested in the seismically vulnerable West Coast of the United States. This animation shows how ShakeAlert worked for the Napa earthquake, and how it could work for a large M7.8 hypothetical earthquake in Southern California.

Ghost forests are part of the evidence that a Great earthquake and devastating tsunami occurred last on January 26th, 1700 in the Pacific Northwest. How do we know this?

Scroll over the bathymetric relief map to learn about the geographic provinces of the Pacific Northwest.

The Pacific Northwest is host to three kinds of earthquakes revealed in this Flash rollover. Subduction zone great earthquakes, shallow crustal quakes, and earthquakes within the subducting plate.

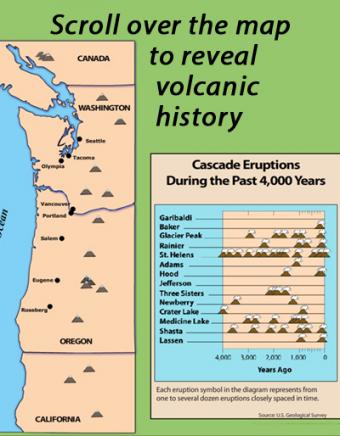

Learn about the volcanoes of the Pacific Northwest Cascade Range mountains by scrolling over individual volcanoes on this interactive map.

Learn how the Pacific Northwest tectonic setting and megathrust earthquake of January 1700 is similar to the catastrophic earthquake in Japan in 2011 by touching icons on this interactive map.

This rollover compares the an earthquake of 1700 in the Pacific Northwest with the 2004 Sumatra earthquake and tsunami. The tectonic settings are similar.

Students work in small groups to analyze and interpret Global Positioning System (GPS) and seismic data related to “mysterious ground motions” first along the northern California coastline, and then in British Columbia. This activity emphasizes the analysis and synthesis of multiple types of data and introduces a mode of fault behavior known as Episodic Tremor and Slip (ETS)