We wrapped up all of our work at the South Pole by early Wednesday morning and were scheduled for a 16:00 departure. During breakfast I looked out one of the galley windows and saw . . . tourists! There is a fair amount of tourist activity at the pole. No one owns the pole, so it not for the US or any other country to say what can or can’t be done, as long as all parties adhere to the Antarctic Treaty. The US government has a policy of not assisting any of the tourist operations. That is, no food, no fuel, no access to the station, etc. So, the planes land, such as the Basler in this photo I took from the galley window on Wednesday morning. The tourists jump out and take pictures at the ceremonial South Pole. Some also stay at the “tourist camp” that you can see in the distance. Someone looked up the prices on line and it is something like $15,000 to spend 5 hours on the continent, including a brief stop at the pole. Prices for a longer visit, including staying at the tourist camp, start at something like $85,000. I am feeling mighty lucky to be here as a scientist. Thanks, NSF!

After watching the tourists for a bit, it was back to the tasks at hand. We took care of our cargo, cleaned our rooms, etc. and had a bit of time to spare. We managed to join an inspection walk through the ice tunnels beneath the station. So here is the really interesting bit. The South Pole Station sits up on stilts above the snow and looks completely self-contained. But in reality, you are only seeing the head of the station. The rest of the station is below the snow line.

There are 1,000’s of feet of ice tunnels deep under the surface where the water pipes and electric lines run. At the far end of these tunnels is a Rod well - which is where the station’s water comes from. Warm clean water is used to make a cavity deep under the ice. The melted ice is pumped out, while more clean water, heated via waste heat from the generators, is continuously pumped back in. In this way clean water is sort of mined out of the ice.

Also under the snow is the generator plant that provides all the electrical power for the station, as well as something like 450,000 gallons of fuel, and a colossal frozen warehouse of food. Sort of like a large, frozen Costco. Truly amazing to see up close all of the life support systems that make the station possible!

The tunnels in the ice are cut with electric chainsaws. In this photo you can still see some of the saw marks on the side. Left alone, the ice would gradually “flow” and close up the tunnels. So the tunnels are regularly maintained and kept open and square. You can probably see a bit of bulge in the sidewall and ceiling.

The temperature in the tunnels is a consistent -56 to -58 degrees. Dang chilly down there. This temperature is due to the cold at pole in the winter. The snow and ice is cooled to far below freezing and maintains this temperature through the relatively “warmer” summer.

The temperature in the tunnels is a consistent -56 to -58 degrees. Dang chilly down there. This temperature is due to the cold at pole in the winter. The snow and ice is cooled to far below freezing and maintains this temperature through the relatively “warmer” summer.

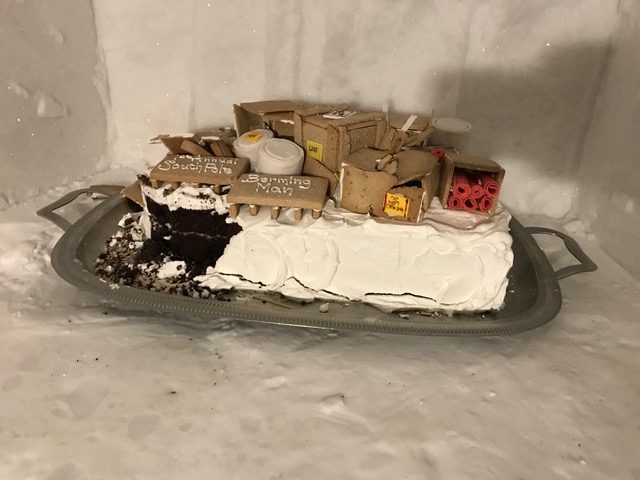

For many years people who work in the tunnels have cut little niches in the wall and created little celebrations of a particular season, or a big event, or some other event that required memorializing. Some of these are really funny while others just plain puzzling. They are a classic feature of the tunnels.

For many years people who work in the tunnels have cut little niches in the wall and created little celebrations of a particular season, or a big event, or some other event that required memorializing. Some of these are really funny while others just plain puzzling. They are a classic feature of the tunnels.

At -58 degrees this cake is going to last for a few centuries!

At -58 degrees this cake is going to last for a few centuries!

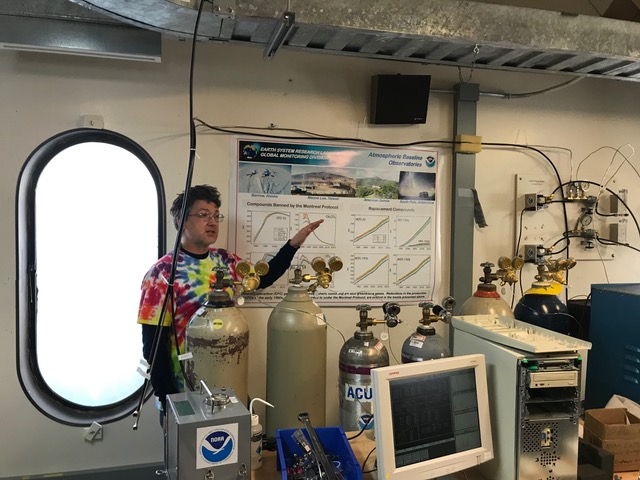

We also got a quick tour of the NOAA atmospheric monitoring station in the “clean air” sector. The clean air sector is upwind from everything else at the station (the winds are evidently super consistent). So here they study CO2 levels in the atmosphere, the ozone layer, the concentration of chlorofluorocarbons, etc. Our flight was arriving soon, but we still had a chance to go up on the roof and collect our own tiny air sample of what the NOAA personnel say is “the cleanest air on Earth”. The scientists there did a great job of explaining the complex interplay that has resulted in the holes in the ozone layer.

We also got a quick tour of the NOAA atmospheric monitoring station in the “clean air” sector. The clean air sector is upwind from everything else at the station (the winds are evidently super consistent). So here they study CO2 levels in the atmosphere, the ozone layer, the concentration of chlorofluorocarbons, etc. Our flight was arriving soon, but we still had a chance to go up on the roof and collect our own tiny air sample of what the NOAA personnel say is “the cleanest air on Earth”. The scientists there did a great job of explaining the complex interplay that has resulted in the holes in the ozone layer.

A poster on the wall of the lab was key to understanding the trends of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) concentrations in the atmosphere as a function of time.

That afternoon our plane arrived as scheduled (we were lucky - the flight for each of the two previous days had been cancelled), and the flight back to McMurdo went by very quick as we raced along with a tail wind. Back in McMurdo it was time to get gear ready for the next big experiment coming through.

That afternoon our plane arrived as scheduled (we were lucky - the flight for each of the two previous days had been cancelled), and the flight back to McMurdo went by very quick as we raced along with a tail wind. Back in McMurdo it was time to get gear ready for the next big experiment coming through.

The photo below shows what it looks like to wait for a plane, South Pole style. Everyone is mostly dressed in their ECW. Then a few minutes before you walk out the door you throw on the rest of the gear (otherwise you would have been sweating buckets while waiting) and away you go. The plane is sitting out front, engines roaring and propellers rotating. One of the cargo masters stretches a line to make sure none of us stray under the props.

Sunday is the normal day off here. But since Christmas is on Tuesday the station is working on Sunday and taking Monday off instead. Sunday was my “boxing” day. No, not dealing with Christmas boxes - it was back to all those station boxes I helped rewire a week or two ago. Each box had to be individually tested to ensure the cables for the satellite communications antenna, GPS antenna, sensor, console, and power were all fully functional. Each box, in turn, was fully outfitted with the station electronics and allowed to run for 20-30 minutes to ensure everything was working.

Sunday is the normal day off here. But since Christmas is on Tuesday the station is working on Sunday and taking Monday off instead. Sunday was my “boxing” day. No, not dealing with Christmas boxes - it was back to all those station boxes I helped rewire a week or two ago. Each box had to be individually tested to ensure the cables for the satellite communications antenna, GPS antenna, sensor, console, and power were all fully functional. Each box, in turn, was fully outfitted with the station electronics and allowed to run for 20-30 minutes to ensure everything was working.

Supposedly the first few penguins of the season have shown up near McMurdo, but I haven’t seen any yet.